Netflix: Disanchoring

Imagine all the margin, it's easy if you try

Netflix reported its fourth-quarter results on Thursday. Here’s the shareholder letter and the transcript.

The headlines focused on Reed Hastings stepping down as co-CEO. That is understandable. Certainly, he is a business legend, having co-founded a DVD-by-mail startup, vanquished larger competitors, and pivoted the business twice, first by pioneering into streaming and later into original content. Netflix now dominates the field with $32 billion of global streaming revenue from over 321 million global household users, including 231 million who are currently paying for it. There is no doubt him stepping down as co-CEO and up to executive chairman is newsworthy. He is on my Mount Rushmore of business leaders.

However, he is leaving the day-to-day in good hands. Ted Sarandos has been co-CEO since 2020 and had been essentially co-running the business for a decade before that. Reed had actually stepped back to focus on philanthropy and his book until he reasserted himself early last year when Netflix’s growth decelerated sharply. But he has relied heavily on Ted and new co-CEO (former COO) Greg Peters for a very long time. Greg spearheaded the creation of the brand new ad business, taking it from an idea to reality in about six months, which is completely absurd. And in any case, Reed will still be involved and available as executive chair and major shareholder. But he is 62 years old, has all the money in the world, and has strong leaders who are more than capable of being formally recognized for they’ve been doing for some time.

That’s why this is a silly question:

The answer to this question is almost always that it’s going to be business as usual. It wouldn’t be, “Yes, we are going to acquire theaters, abandon original content, and plow streaming profits back into the DVD business. Reed hated these ideas of ours, so naturally he put us in charge. And now we’re free to execute on them (even though he is executive chair).”

I think Reed, Ted, and Greg are very much on the same page strategically. While Greg alluded to the fact that others internally warmed up to advertising sooner than Reed did, the team got to the same place eventually. And they have been giving strong signals that they are very open-minded about strategies and tactics in the years ahead.

For example, live sports is on the table if they can figure out a monetization framework that works for Netflix. The current model is to amortize fixed cost content across a growing base of subscriber (and now ad) revenue, which drives margins up over time. Renting sports rights that reprice higher every few years prevents that. That’s behind Ted’s comment that they “are not anti-sports, they are pro-profits.” Renting sports rights would also be a missed opportunity because Netflix has the unique power to significantly boost fan interest and engagement in the sport through their docuseries projects, but it wouldn’t execute that plan if it would drive up its own content costs.

Look at Drive to Survive, Netflix’s F1 docuseries that completely blew up the sport. In 2019, before DtS, ESPN was paying $5 million per year for the F1 TV rights. Thanks largely to DtS, last year, it agreed to pay $75-$90 million per year. An astounding 53% of F1 fans said DtS played a role in them becoming fans of the sport. Of course, Netflix does not want to give the sports leagues these gifts for free. Naturally, it wants to maximize its own participation in the value it creates.

We don’t know the economic terms for DtS, Break Point, the new tennis docuseries, or the several other sports docuseries (golf, rugby, Tour de France, World Cup soccer) that are being released this year. But I would expect each of them to increase fan interest and engagement with the respective sports just as DtS has done for F1. So, and I’ve written about this a few times, I don’t think Netflix should be paying for this content. I think the leagues should be funding the content creation, giving Netflix the perpetual rights, and compensating Netflix for making it available to its roughly one billion global viewers. It is unbelievably effective advertising—roughly 10 hours of advertising per season to the millions of people who watch it—which increases live viewership, ticket sales, concession sales, and overall fan engagement. It is a proven model, in my view, driven by Netflix’s unprecedented scale and engagement. Even Queen’s Gambit completely blew up sales for chess sets and books:

Which party—F1 or Netflix—benefits more from DtS being on Netflix? Remember, 53% of F1 fans cited DtS as a reason they became fans. And the TV rights skyrocketed in value by 15-18x in three years. On the other hand, DtS almost certainly accounts for a fraction of 1% of Netflix viewing hours. It is one drop in the content bucket. So who needs this arrangement more? The answer should dictate who pays who.

Buying Leagues?

One very direct way for Netflix to participate in this value creation would be to own the leagues themselves. Major sports leagues (NFL, MLB, etc.) are not feasible, but there are small sports leagues that could be on the table. This WSJ story from November discussed this in some detail, including the negotiations to buy the World Surf League that fell through.

On the call, they were asked about WWE, which is for sale.

Owning WWE would mean they could maximize the monetization of it however they wish without being at the mercy of the ever-increasing cost of the rights every few years. I don’t think there is another bidder who could create more value out of something like WWE than Netflix. No one else can create a WWE docuseries that would be seen by as many viewers globally. A WWE docuseries would increase interest and engagement in the regular WWE programming on Netflix, which would include ad-supported live events. The fact that the value of the F1 television rights increased by 15x-18x in only three years gives at least some sense of how much more ad revenue ESPN expects to earn from airing it in a post-DtS world. While I would not forecast similar increases for WWE TV rights in a post-WWE docuseries world, I do think ad revenue benefits of some magnitude would accrue to Netflix from owning something like WWE. But importantly, it would be much better positioned than ESPN is with F1 because the WWE IP would be a wholly-owned fixed cost. That’s exactly what Ted is talking about—when the whole world is their oyster, when they could conceivably have a billion or more global households and perhaps half the global population watching Netflix one day, they can create far more shareholder value by having fixed cost content rather than variable cost content.

Another example of being open-minded about new strategies is free ad-supported television. This is the domain of Pluto, Tubi, Roku, Freevee (Amazon) and others. Now that Netflix is in the ad business, it opens up opportunities like this.

That’s not a tepid answer to that question. To me, that’s “We’ll probably do it, but next year.”

Netflix is also getting into live programming. It is starting with a live Chris Rock stand up special in early March. I wouldn’t be surprised if in five years Netflix has regular live programming. Comedy specials, game show finales, and live sports are just a few of the genres that could make sense for live.

Disanchoring

I think it’s easy and natural for people to anchor on a business the way it is—in this case, Netflix = SVOD. You pay monthly for on-demand streaming content. That’s what it is. In contrast, I think it’s unnatural and uncomfortable for most to consider how different a business could look in the future—both as a service and its financial model. For one thing, the future is uncertain and it’s easy to be wrong about it so most probably don’t bother. A few years in the future is also beyond the time horizon of most market participants.

But for those of us who think of ourselves as long-term investors, it seems impossible to escape the fact that we are betting on the future. We are either betting that a business will mean revert or will change in some way beyond what market expectations imply. It can be an uncomfortable reality that investors have to disanchor themselves from the present and imagine themselves in the future in order to bet on it.

Netflix could look very different in five years. On the call, Greg said this about the future scale of the ad business:

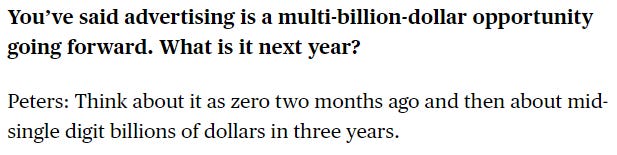

And then in a Bloomberg interview released after earnings, he was asked how big the ad business could be.

Going from an idea to ~$5 billion of ad revenue and growing in 3.5 years would not be a bad start. It makes me wonder how much free ad-supported television is factoring into that figure.

In Netflix: Turning on the Spigots (July 2022), I wrote the following about a free ad-supported offering:

I wonder if Ted and Greg could be thinking similarly now that they’ve said they’re looking at free ad-supported TV. Facebook and YouTube are global and free to the consumer—just like a free Netflix tier would be—and they have close to 3 billion global MAUs each. How many would Netflix have in a free ad-supported offering? I think there’s probably close to 1 billion already watching right now (as distinct from households)—could there be another billion or more free ad-supported users? And how much more profitable would that be with fixed cost content rather than with variable cost content like YouTube has?

I think the answer to that primarily comes down to two things—total revenue and content costs. How much global subscription and advertising revenue could Netflix support with $17 billion of annual content spending? Can they increase revenue by 50% through advertising and paid sharing while holding content costs steady? How much more revenue, if any, could it support with $20 billion or $25 billion of content spending?

With Netflix, it’s helpful to think about the gap between revenue per sub per month (ARM) versus content amortization per sub per month as the driver of the bulk of the long-term operating leverage. For example, over the last five years, ARM has compounded at a 4.5% annual rate while content amortization per sub per month has compounded at 0.2%. Wait, you might ask, hasn’t content spending more than doubled (from $6.2 billion to $14.0 billion) over that period? Yes, but the denominator (subs) has grown just as fast.

That’s the beauty of the model that I think most people miss or underappreciate. Netflix can spend more on content to provide a better service to every subscriber, which drives engagement and then pricing power and even more revenue, while not spending any more on content on a per-subscriber basis. That drives margins way up over the long term. And this is not easy to do for smaller competitors who are losing money and not quite all-in on streaming because they are managing legacy businesses in decline.

I’d suggest disanchoring from current margins and playing this movie out over many years. It has big implications for what the business is worth.

Reflecting on 2022

Netflix was trading at 15x forward earnings as recently as June. And 11x 2024 consensus earnings. I would argue that unusually depressed valuations like that were only possible because most people could not see anything other than what Netflix looked like, on the surface, in that moment: a former growth business that saw its growth rate collapse amid increasing competition. Few were able to disanchor from that characterization because imagining, let alone betting on, a future that looks very different than what they perceived is, again, unnatural and uncomfortable.

It also required a strong understanding of the business, a truly long-term perspective, and a willingness to ignore what almost everyone was saying. That’s hard. Few were positioned to do that. But that’s a good example of how and why stocks can get enormously mispriced. At $360 per share, NFLX is up 121% from its May 2022 low.

The reality was Netflix was hampered by “near-term limiters” on its growth, not long-term limiters. By allowing rampant password sharing, Netflix had started to saturate its near-term subscriber opportunity. While it had 221 million paid subs, there were another 100 million-plus using it for free, and the near-term growth opportunity from 320 million users was more limited. And by not having an advertising offering, Netflix was leaving loads of money on the table.

Like I wrote in July, buying NFLX down 75% right before it entered the ad business and before paid sharing looked like like an incredible out-of-favor opportunity.

The long-term limiters on the business—global broadband household and connected TV penetration—appear to leave plenty of headroom in the years ahead. Netflix uniquely has the scale, budget, expertise and experience to create content for everyone all around the world. And this is a business that clearly gets better with scale both from leveraging fixed cost content and from getting better terms on certain types of content, as discussed earlier.

The Quarter

Many of you can probably tell that 90 days of business results are less interesting to me than imagining what Netflix can look like in the future. Certainly, I want the business to remain more or less on track with my long-term vision or, at the very least, there should be good explanations why it has temporarily gone off track, like it did last year. But the exact quarterly numbers could be anything within a range without me caring too much. Here’s the quick recap.

Revenue grew 1.9% year-over-year, which beat guidance of 0.9%. On a constant currency basis, revenue grew 10%, which also beat the 9% guidance. Average paid subs grew 4.2% year-over-year while average revenue per member (“ARM”) declined 2% but increased 5% ex-currency. Paid net adds of 7.7 million handily beat the 4.5 million guidance due to “strong acquisition and retention.” I think 10% ex-currency revenue growth is fine considering the ad business was only two months old and still very much in “crawl” mode and paid sharing hadn’t begun.

Operating income of $550 million beat the $330 million guidance due to the revenue outperformance and slower-than-expected hiring. Fourth-quarter operating margin was 7.0% versus the 4.2% guidance.

Currency was a meaningful headwind on the business last year. 2022 revenue would have been $962 million higher if currencies had remained unchanged while operating profit would have been $748 million higher.

As for guidance, 1Q revenue is expected to grow 4% or 8% at constant currency. That’s driven by modest growth in average paid subs and ARM. There was some pull forward of subs in 4Q, presumably from the initial ad-tier roll out.

Given the ramping up of the ad tier and rollout of paid sharing (later in 1Q), management expects revenue growth to accelerate throughout 2023 on a constant currency basis. 2Q is usually a weak quarter but should be stronger than 1Q this year. Operating profit should grow and operating margins should expand through the year barring any wild currency swings. Specifically, management was previously guiding to 2022 and 2023 operating margins of 19%-20% at beginning of 2022 exchange rates, but is now raising 2023 to 21%-22% on the same basis. Obviously, currencies have moved against them since then, but that does show an underlying profitability improvement. At current exchange rates, full year operating margin is expected to be 18%-20%.

Given the likelihood of constant currency revenue growth accelerating throughout the year, we could see something like 8%, 12%, 14%, 16% on that basis.

Call Highlights

One thing that jumped out at me from the call was this comment from Greg about the extent to which their ad business will compete with Google and Meta in terms of targeting capabilities:

“Not really… we won’t be well suited to compete with that for at least some time to come,” actually means “Yes… we will be well suited to compete with that in the future.” Clearly, management thinks their ad business is going to vastly improve its targeting and measurement over time. That seems to mean higher CPMs than the traditional TV advertising pool of today, which is already a $180 billion market ex-China and Russia. It will be super interesting to see how this evolves.

The Must-Seeness

Ted made a comment that it’s “the must-seeness of the content that will make the paid sharing initiative work.” This is exactly my point of view. For a while, Rich Greenfield—who I usually agree with about Netflix—was saying that Netflix’s woes were due to not enough hit content. That more hit content would get them out of their 2022 rut.

I disagreed with that because Netflix had hit content that wasn’t moving the subscriber needle. For example, in the two quarters that the two installments of Stranger Things 4 were released (2Q and 3Q 2022), Netflix lost 1.2 million subs in UCAN and gained just 1.4 million subs globally. Yet ST4 was a smash hit:

I believe hit content wasn’t moving the needle because, again, Netflix had gotten closer to fully penetrating its near-term market potential when including the 100+ million households that were watching for free. That meant there were 321 million households already watching. And 321 million meant some markets were closer to fully penetrating their current (not necessarily future) broadband household and connected TV market.

But imagine if the 100 million were to suddenly lose access to Netflix. And then a Stranger Things 5 or a Squid Game 2 or the next iteration of Wednesday or the next surprise must-see global phenomenon comes out. Many of those would start paying for Netflix. So I never thought it was “Netflix just needs more hit content,” but instead “Netflix needs the 100 million-plus freeloading households who get cut off to feel that extreme FOMO when hit content is released.”

Obviously, Rich is right in the sense that more hit content is better than less. But when more of the world that has a broadband connection and a connected TV is already watching, paid or freeloading, it just doesn’t allow for 27 million paid net adds annually. But Netflix has almost four years of that kind of growth potential available just by monetizing via paid sharing.

Scenario Analysis and Valuation

Obviously, Netflix is pricing in higher expectations than it was six months ago. But it’s also pricing in much lower expectations than it was two years ago when revenue was growing faster but there was no ad business or paid sharing coming.

I have more information to incorporate into my scenarios. For one thing, management expects ~$5 billion of ad revenue within three years. I hadn’t previously accounted for any advertising revenue in my scenarios. I wonder how much of that is incremental versus cannibalistic with paid subscribers. So far, it seems mostly incremental.

This post is getting long so I’ll post my updated scenarios and valuation work in another post soon.

Disclosure: Long NFLX

Disclaimer: This post is for entertainment purposes only and is not a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Everything I write could be completely wrong and the stock I’m writing about could go to $0. Rely entirely on your own research and investment judgement.

Great post IE!