Carvana: On The Verge of Step 3

Can they accelerate volume growth while maintaining good unit economics?

A lot has happened since my last Carvana update in Carvana: Feedback Loops. Let’s run through it.

On July 18th, Carvana announced it was moving up its second-quarter earnings release date from August 3rd to the following morning. I thought this unusual move had to be driven by some sort of imminent capital raise and/or debt restructuring announcement.

The following morning the company announced its second-quarter results in conjunction with, sure enough, the launch of a debt exchange offer with the support of over 90% of its noteholders. Essentially, Carvana is issuing new notes with more flexible terms in exchange for most of its current notes and executing a cash tender offer for its 2025 notes. The expiration of the exchange offer was on Wednesday, August 30th, and Carvana announced yesterday morning that it is completing the exchange offers with 96% of its current noteholders participating. With these finalized terms, it is reducing the face value of its notes by $1.325 billion, extending the maturities, and reducing required cash interest payments by over $455 million annually for each the next two years in favor of PIK debt.

In exchange for that additional flexibility, the new notes will be backed by both Carvana and ADESA assets, which provides noteholders with additional collateral, and the new notes will have higher interest rates. As a condition of the debt exchange, management raised $350 million of equity at $46.31 per share, of which $126 million came from the Garcias. The proceeds are being used primarily for additional cash consideration to retire the existing notes.

So what does this mean? Big picture, Carvana is gaining a lot more flexibility by not having to pay any cash interest in the first year and having the option to pay PIK in lieu of cash interest in the second year. In my view—and this is far above consensus, which has been consistently way behind the curve on Carvana’s operational improvements—the company is pretty clearly on the path to generating over $500 million of adjusted EBITDA over the next 12 months. With no required cash interest on the new notes for two years, that level of adjusted EBITDA would easily cover the interest on its inventory and finance receivable facilities plus capex for this period, leading to nicely positive core free cash flow (even after deducting stock-based compensation). Certainly, the face value of the new notes will grow during this 1-2 year period due to the PIK debt. This is akin to kicking the can down the road. But this cash interest holiday gives Carvana two years to ramp retail unit volume—at its now strong incremental unit economics—before the new notes revert to a cash interest requirement.

Two years is a long time. Carvana will likely formally begin Step 3—returning to growth—early next year. Selling more units at its already record-high unit economics through the existing high fixed cost infrastructure is likely to lead to strong growth in adjusted EBITDA from already record levels today. At that point, the business is likely to be in a much stronger position to pay cash interest again. However, the more likely outcome is the stock soars over this two year period, allowing management to eventually issue some new equity at a higher price via their ATM offering in a minimally-dilutive way. That would allow them to retire some of their new debt early before the PIK period ends. Under the terms of their Transition Support Agreement, they can retire the new 2028 notes after only one year at par plus half a coupon and the 2030 notes after two years on the same terms. Management has strongly suggested that is their game plan.

Carvana is clearly on the path out of the woods in terms of its balance sheet and liquidity. Management has plenty of time to finish tweaking the business, return to growth, and start generating serious cash before it would begin to owe cash interest on the new notes.

Operational Improvements

While the debt exchange captured most of the headlines, Carvana’s rapidly improving operating results are the bigger story. The second quarter showed continued progress holding retail units relatively steady while making large, undeniable progress on improving the unit economics. Non-GAAP GPU was an astounding and record-breaking $7,030 in the quarter. Even excluding the $900 of non-recurring items that benefited the quarter—$650 driven by loan sales in excess of originations as they drive down the large backlog of loans held for sale and $250 from a retail inventory allowance adjustment as they sold through cars that had been written down in the fourth quarter—$6,130 of non-GAAP GPU is still a record-breaking number. It is about $2,500 higher than the company reported in the year-ago quarter and almost $1,000 more than it reported in the same quarter in 2021—the previous high water mark.

The single largest driver of this increase in GPU was getting inventory back in line with the current sales volume. It had been way out of whack because management had prepared the company for significant growth that did not materialize last year. That left Carvana with way too much inventory last year, which increased turn times and depreciation per unit, minimizing GPU. Management has spent the last year getting inventory back into balance, which has had the opposite effect of reducing turn times and therefore depreciation per unit, which increased GPU. Average days to sale fell to 91 in the second quarter and is expected to reach 65-75 days in the third quarter before getting back to the low-to-mid 60s beyond that.

The other major factors behind the increase in GPU have been lowering costs in the IRCs and logistics network, buying more cars from customers, which are more profitable than via the wholesale channel, and generating extra revenue streams like delivery fees. CFO Mark Jenkins probably spent the majority of his talk at the J.P. Morgan conference last week discussing why non-GAAP retail GPU in the $2,200-$2,800 range is sustainable.

On the SG&A side, Carvana was able to reduce non-GAAP SG&A by another $21 million sequentially last quarter to $383 million. Once again, management’s prior guidance—this time calling for flat non-GAAP SG&A quarter-over-quarter—proved conservative. Notably, none of the $21 million decline was driven by advertising, which increased by $1 million sequentially. Compensation and benefits declined $14 million, market occupancy declined $3 million, and logistics declined by $6 million. With 76,530 retail units sold in the quarter, non-GAAP SG&A per unit was $5,005.

Between $7,030 of non-GAAP GPU and $5,005 of non-GAAP SG&A per unit, Carvana had $2,025 of adjusted EBITDA per unit in the quarter. Even without the non-recurring GPU items, that would have been $1,125 per unit. Adjusted EBITDA per incremental unit is much higher though because variable costs are only a portion of overall costs. Ernie discussed how that means incremental growth is already nicely profitable, but there is still a bit more work to do before really ramping growth.

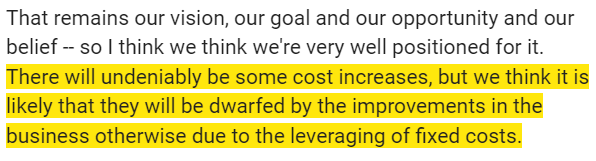

I think adjusted EBITDA per unit still has a long way to go. Most of the opportunities on the GPU side seem to have been captured at this point, but the bigger remaining opportunity is on the SG&A side. On the second-quarter call, Ernie said:

That’s interesting because over the last year Carvana was able to reduce the non-GAAP SG&A quarterly run-rate by $266 million (!) or an annual run-rate of over $1 billion. So what’s left to come with the current SG&A plan over the next 12 months? Management didn’t say but I think we’ll see the fixed components within Other SG&A come down over the next few quarters. Here’s Mark addressing that on the second-quarter call:

Overall, the three drivers of reducing non-GAAP SG&A per unit are 1) reducing variable SG&A, 2) reducing fixed SG&A within the Other SG&A bucket (the above quote), and 3) returning to growth, which drives fixed cost leverage. Here’s Mark explaining this on the second-quarter call:

How much better can non-GAAP SG&A per unit get? Well, if we go back to the operating plan slide deck they released in August of 2022, management gave a mid-term non-GAAP SG&A per unit target of $2,900-$3,100 (see below). I think they had something like 600,000 units of volume in mind when they put these numbers together, which probably makes that mid-term goal realistic for 2026 or so.

2024 and 2025

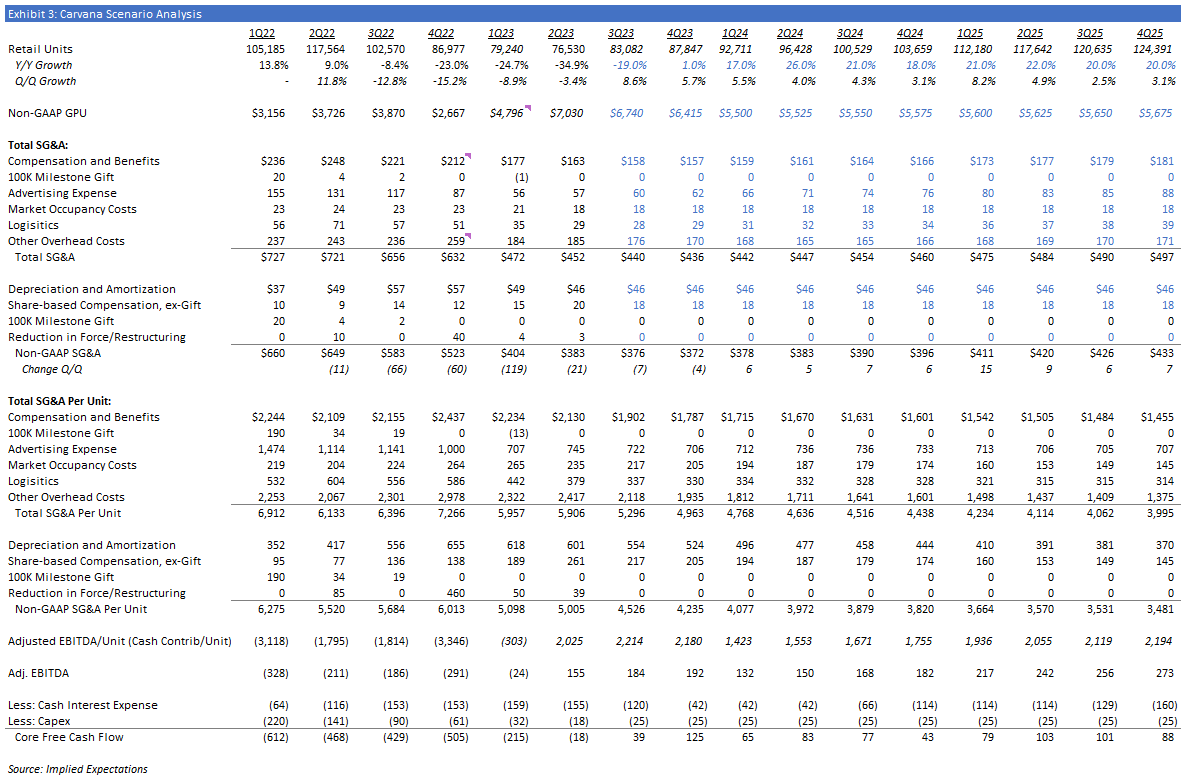

In 2024, I can imagine Carvana selling something like 393,000 retail units, doing about $5,500 of non-GAAP GPU, and maybe $1.55 billion of non-GAAP SG&A or about $3,933 per unit. Adjusted EBITDA per unit would be about $1,600 and adjusted EBIDTA would be about $632 million.

In 2025, I can imagine the business selling something like 475,000 retail units, doing something similar on non-GAAP GPU, and maybe $1.7 billion of non-GAAP SG&A as they return to growth, which would work out to about $3,550 per unit or $1,750 on an incremental basis. Adjusted EBITDA per unit would be about $2,080 and Adjusted EBITDA would be $987 million. The key here is variable SG&A per unit is much lower than overall SG&A per unit because they will leverage fixed costs, contributing to higher profitability.

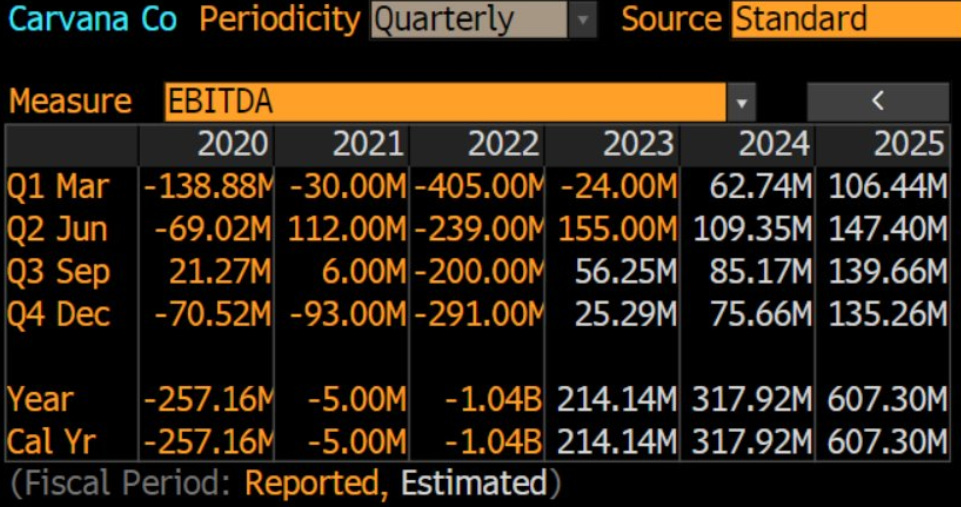

For context, the current consensus is $318 million and $607 million of adjusted EBITDA for each of the next two years, respectively.

I’ve written several times this year how the sell-side is way behind the curve on Carvana. This is the third or fourth time in a row I’ve written about how consensus adjusted EBITDA for the next quarter ($56m) is actually below management’s guidance ($75m+). And every time, management has beaten both consensus and their guidance. The longer term estimates make even less sense if you believe that management can return the business to volume growth. Because non-GAAP GPU is at all-time highs thanks to their operational improvements. And the variable costs to fulfill the next unit are modest thanks to regionalizing inventory, integrating ADESA locations, maximizing vending machine and market hub pick ups, which is cheaper than home delivery, and improved truck utilization. So the next retail unit sold appears to have a very high contribution profit. As a result, we are likely to see meaningful adjusted EBITDA growth as they begin to layer volume growth on top of those all-time high unit economics, even assuming costs of returning to growth.

Looking Further Ahead

It’s hard to know exactly how fast Carvana intends to grow, but in 2026 I can imagine something around 600,000 retail units at $2,300 of adjusted EBITDA per unit. That might consist of $5,500 of non-GAAP GPU as investments in growth are largely offset by fixed cost leverage in the IRCs and maybe some wholesale business growth, including some volume recovery at ADESA’s auction business. And we could see non-GAAP SG&A per unit in to the low $3,000s, essentially in line with management’s “mid-term goal” of $2,900-$3,100, taking into consideration some inflation, that they disclosed exactly one year ago. See above.

600,000 units at $2,300 per unit would be $1.38 billion of adjusted EBITDA. That kind of earnings power is not on anyone’s radar right now. At $50 per share, Carvana’s market cap, including the recently issued shares, is $9.9 billion. Including the face value of the new notes, the enterprise value is around $14 billion. That will grow over the next year or two as PIK interest gets added, but that would add $1.2 billion to the debt at most, so close to $15 billion.

While $1.4 billion of adjusted EBITDA in a few years is exciting, what’s more exciting is the growth opportunity beyond 600,000 units. That level is still only ~1.5% national market share. Given Carvana’s unique and advantaged vertically-integrated model and superior customer experience and value proposition, there is little reason to doubt they can continue to gain meaningful market share over time when back in growth mode. This is a company that grew over 100% annually for years when the used car market was not growing, primarily because of those advantages. This is a company that reached 3.5% market share in its oldest market, Atlanta. This is a company with a history of launching new market cohorts that scale faster than previous ones.

While I don’t expect triple-digit growth again, I do think Carvana’s many advantages will allow it to take meaningful market share and grow significantly over time. Consider how the company is now rolling out same-day delivery in more and more markets. That would be very hard for a competitor to achieve economically without local reconditioning and logistics assets and meaningful scale. I can imagine a long runway of perhaps 20%-40% annual volume growth. The business has reconditioning capacity for up to 1.4 million retail units today versus it’s annual run-rate around 325k-350k. And with the 56 acquired ADESA locations, Carvana can have the capacity to recondition up to 3 million retail units annually as they make certain capital investments. It would take many years, but 3 million units at perhaps $3,000 adjusted EBITDA per unit with that kind of scale would be $9 billion of annual adjusted EBITDA. Even still, there is no law that says the natural scaled consolidator of this market must be capped at a single-digit market share. The largest player in most retail verticals has market share a multiple of that.

So there is a lot of upside potential here both short-term and long-term, but the market still seems to doubt that Carvana can return to growth at all. Or if they do the gains made on the unit economics will collapse and the company will return to cash-burning growth mode again. If you believe either of those things, then you probably think the debt exchange is just kicking the can down the road and the company will be under pressure once the PIK interest reverts to cash interest after two years. Obviously, I disagree but that’s why the stock isn’t higher than it is.

Everything I see suggests Carvana can begin to grow again while maintaining strong unit economics. In fact, the daily data provided by Alternative Alpha suggests growth is already beginning to pick up. And the positive spread between sold unit ASPs and their Kelley Blue Book values is remaining wide. That’s positive for GPU. This is also while inventory levels appear flat to even down slightly. Higher sales at these unit economics are fantastic, but are even better to the extent inventory doesn’t grow because it means faster turn times, lower days to sale, and higher GPU. This seems roughly consistent with management’s comments at the J.P. Morgan conference indicating that average days to sale of 91 in the second-quarter would drop to 65-75 days in the third quarter before targeting low to mid 60’s beyond that. Given average retail unit depreciation of $10 per day, a 21 day decline in average days to sale suggests around a $210 GPU benefit quarter-over-quarter. And perhaps a bit more after that getting down to low to mid 60s. That said, inventory will have to grow eventually when average days to sale reaches its optimal level. And of course, that will be bullish because it implies both 1) the unit economics reaching the limits of its potential and 2) an almost certain sales acceleration.

Updated Model

Here’s my updated short-term model through 2025.

Since last time, I’ve raised my non-GAAP GPU estimates for the larger than usual loan sales as Carvana sells down its backlog of loans and for some of the sustainable operational gains made that Mark Jenkins discussed at the J.P. Morgan conference. While the former benefit is temporary the latter should be mostly sustainable.

On non-GAAP SG&A, I think they can continue to reduce variable costs per unit while also reducing fixed costs in Other SG&A (corporate, tech, facilities) as Mark discussed in the “three primary drivers” quote I quoted above.

I have overall non-GAAP SG&A declining modestly for another two quarters before beginning to rise with volume growth. Under the surface, I think there will be larger reductions in Other SG&A—as you can see above—that could be offset by variable costs in comp and ben, advertising, and logistics as volume growth returns.

However, I am optimistic that the costs of preparing for future growth can be more modest than they have been in the past. Ernie made the following comment that jumped out to me:

Ernie is saying that Carvana’s variable costs to sell a car are much more efficient today. For example, if it used to cost them $1 to sell a car and they wanted to be positioned to sell two more cars—preparing for future growth—they would have to invest $2. But now that Carvana is much more efficient, it might only cost them $0.50 to sell a car, which means positioning the business to sell two cars only costs $1 instead of $2. In other words, Carvana is going to invest for future growth but they won’t have to invest as much as they used to to achieve the same growth. That’s interesting because there seems to be lots of consternation about how sustainable these all-time high unit economics are if or when they return to growth.

Big Picture

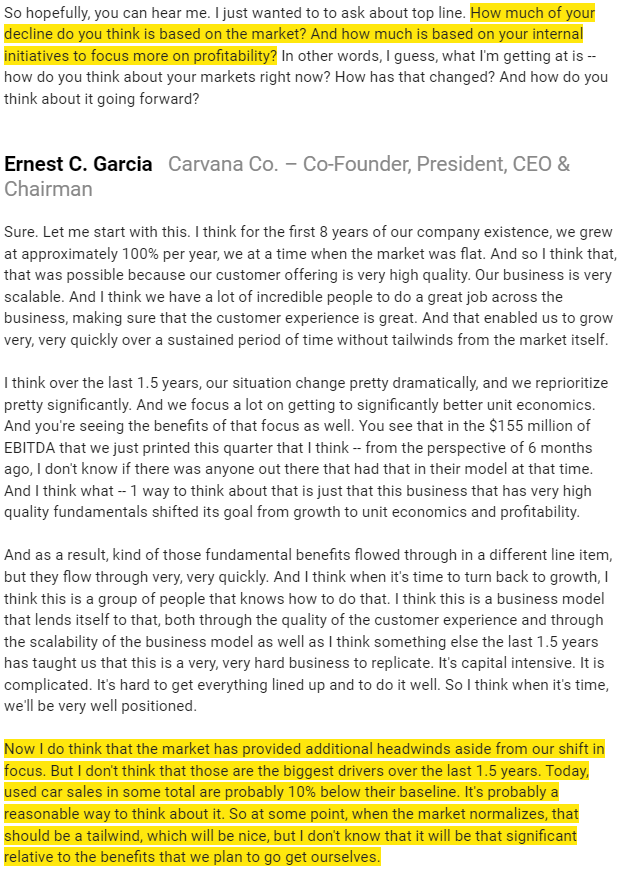

The big picture is that Carvana is maximizing the unit economics right now and then will begin to pull the unit growth lever. That may be starting to happen already. Some might be skeptical that they can just grow more because they want to, but I think it’s pretty clear they can. This is a company that was growing retail units at a pace of over 100% year-over-year for a very long time. That was while the U.S. used car market volumes were flat. How did they do it? It’s pretty simple: a great and differentiated customer experience, the best overall value proposition in the business, and investing ahead of demand growth.

Others might say, “Well sure they can have good unit economics when they’re not growing, but they’ll fall apart when they start growing again.” I don’t think so. First, I don’t think management is going to be shooting for 100% year-over-year growth, which means they won’t need to invest ahead of demand quite as much as they once did. Second, I think they have been carefully and deliberately structuring the business to minimize the variable costs of fulfillment as Ernie discussed in his “$0.50 to sell a car” comment. Third, they are running the business at an annual run-rate of about 320,000 retail units, which is only about 25% of their reconditioning capacity assuming full staffing levels. By minimizing variable costs and leveraging their high fixed costs, the next car sold has a meaningful contribution profit. Ernie thinks they will need some incremental investments in growth but those will be “dwarfed” by the operating leverage from running more units over their fixed cost infrastructure.

I think the biggest disconnect between my near-term views and the market’s is that the market is underappreciating how much is within their control. I’ll leave you with this quote from Ernie explaining how the majority of their volume declines over the last year have been self-inflicted due to their prioritization of efficiency at all costs. That was within their control just as turning the growth dials up when they are ready will be as well.

Disclosure: Long CVNA

Disclaimer: This post is for entertainment purposes only and is not a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Everything I write could be completely wrong and the stock I’m writing about could go to $0. Rely entirely on your own research and investment judgement.

Excellent work - reasonable destination analysis that the market has been missing for the past year. I think some of the analysts are starting to track and will be interesting to see stock prices respond to ratings upgrades following execution. Invest well!

Extremely good writeup. Thank you so much.