Netflix: Welcoming the Arms Dealers

Netflix reported its third-quarter results on October 18th. Here is the shareholder letter.

I thought this was a fantastic start to the letter:

Revenue grew 8% year-over-year as reported and in constant currency terms. That was due to the 9% year-over-year gain in average paid memberships and the 1% decrease in ARM (“average revenue per member”), which was the result of growth in lower-ARM countries, limited price increases, and some shift in plan mix.

As for guidance, management expects accelerating revenue growth into the fourth quarter with guidance of 11% growth or 12% on a constant currency basis. The quarter should have a similar number of paid net adds—9 million—plus or minus a few million, and ARM should be flattish.

Essentially, Netflix is benefiting from the gradual rollout of paid sharing whereby password borrowers who want to continue watching Netflix must either transfer to their own new paid accounts or become a paid extra member on the original account. This boosts both the paid subscriber base through new accounts as well as ARM through extra members. They are carefully rolling it out in cohorts so they can measure results and tweak the experience as needed to maximize results. Management expects to see the benefits of this for several quarters to come.

Meanwhile, the writer’s strike is delaying content spending. Cash content spending will be about $13 billion this year, down from $16.7 billion last year, which is helping to boost near-term cash flow. Content amortization is tracking towards $13 or $14 billion as well, which is flat to down slightly from last year. When revenues are growing and content amortization, the single largest expense, is flat to down, margins increase. That’s part of why we’re seeing operating income and free cash flow surge this year. Netflix is on track to generate $6.6 billion of operating income and $6.5 billion of free cash flow this year.

As for the ad tier, it is just getting started but is coming along nicely with 70% quarter-over-quarter growth and a 30% mix of new sign ups in countries that offer the ad tier. The key for Netflix’s advertising business is scale. The more eyeballs are watching, the more attractive Netflix is as a place for advertising dollars. And this is a $180 billion ad market for linear/connected TV, excluding China and Russia. It feels inevitable to me that Netflix will have meaningful ad revenues in the long run.

To get there, management wants to nudge more subscribers towards the $6.99 ad tier. That’s why they stopped offering the Basic ad-free tier to new sign ups and partially why they just raised the price of the Basic ad-free tier to existing subscribers. New customers in the U.S. are offered the $6.99 ad-tier, the $15.49 Standard ad-free tier, and $22.99 Premium ad-free tier. Clearly, they are widening the gap between the $6.99 ad-tier and everything else to drive more people into the ad tier. And in the shareholder letter, management suggested an “even wider” range.

Recall management said the $6.99 ad tier was already monetizing better than the $15.49 Standard tier several months ago, so trade down is already nicely accretive. I believe the ad tier monetization will continue to improve and will eventually monetize comparably or better to the Premium tier, if it isn’t already. That should give management more freedom to raise ad-free prices because any potential trade down to the ad tier is accretive. I think that is behind the “even wider” comment.

Big Picture

It was always a bull case for Netflix that competitive streamers would come around to the realization that streaming on a smaller scale with less robust engagement metrics is a very difficult business. And that they would eventually shift more of their business back to arms dealer mode by licensing content to Netflix. After all, licensing revenue is virtually all profit, which can look tempting compared to burning billions of dollars of shareholders’ money on streaming.

For a while there as Disney+, HBO Max, and others were ramping up and seeing decent subscriber growth, there wasn’t much talk of this. At the time, I thought it was more likely than not at some point, but I assumed it might take 3-5 years or maybe longer before this might potentially play out. Well, it’s been happening and began sooner than I had expected.

It wasn’t that long ago when all the talk was about how Netflix was screwed because its competitors were pulling content in favor of their own streaming services. Shows like The Office and Friends were pulled and put on Peacock and HBO Max (now known as Max), respectively. Netflix would no longer benefit from its competitors’ content. And because “content is king,” Netflix was doomed.

Well, well, well, how the turntables…

Recently, HBO has also licensed seasons of Ballers, Band of Brothers, The Pacific, Insecure, and Six Feet Under to Netflix. I think most of the rationale is to capture that sweet licensing revenue and offset some of the service’s cash burn. But it’s also about exposure. By making the first season of a show available to Netflix’s massive audience, the hope is some of them will sign up for Max to watch the remaining seasons and potentially stick around. I’m skeptical that’s going to be very effective. For one thing, the primary reason there’s more licensing to Netflix now is because they have to to address cash burn problems. It seems clear that making more of your content non-exclusive and licensing it to your largest competitor wouldn’t be the optimal approach if their financials were sound. It certainly wasn’t the original game plan four years ago when these services launched. But streaming is harder than Netflix made it look. And times have changed. There is less patience for eternal cash burn in the name of growth.

I think this has important competitive implications. It seems to me that a lot of sub-scale, lower engagement, cash burning services are doing three things: 1) reallocating content from streaming to legacy distribution, 2) licensing once-exclusive content to Netflix, and 3) raising prices. Those seem to be rational decisions to improve cash burn and reach profitability. But if you were a streaming exec at one of these and you wanted to make your service’s value proposition worse, what would you do? You’d 1) remove content, 2) you’d make more of your once-exclusive content available on competitive services, and 3) you’d raise prices. Making your value proposition worse is not usually a good way to retain subscribers and attract new ones. Yet this is the most rational choice they have given the circumstances.

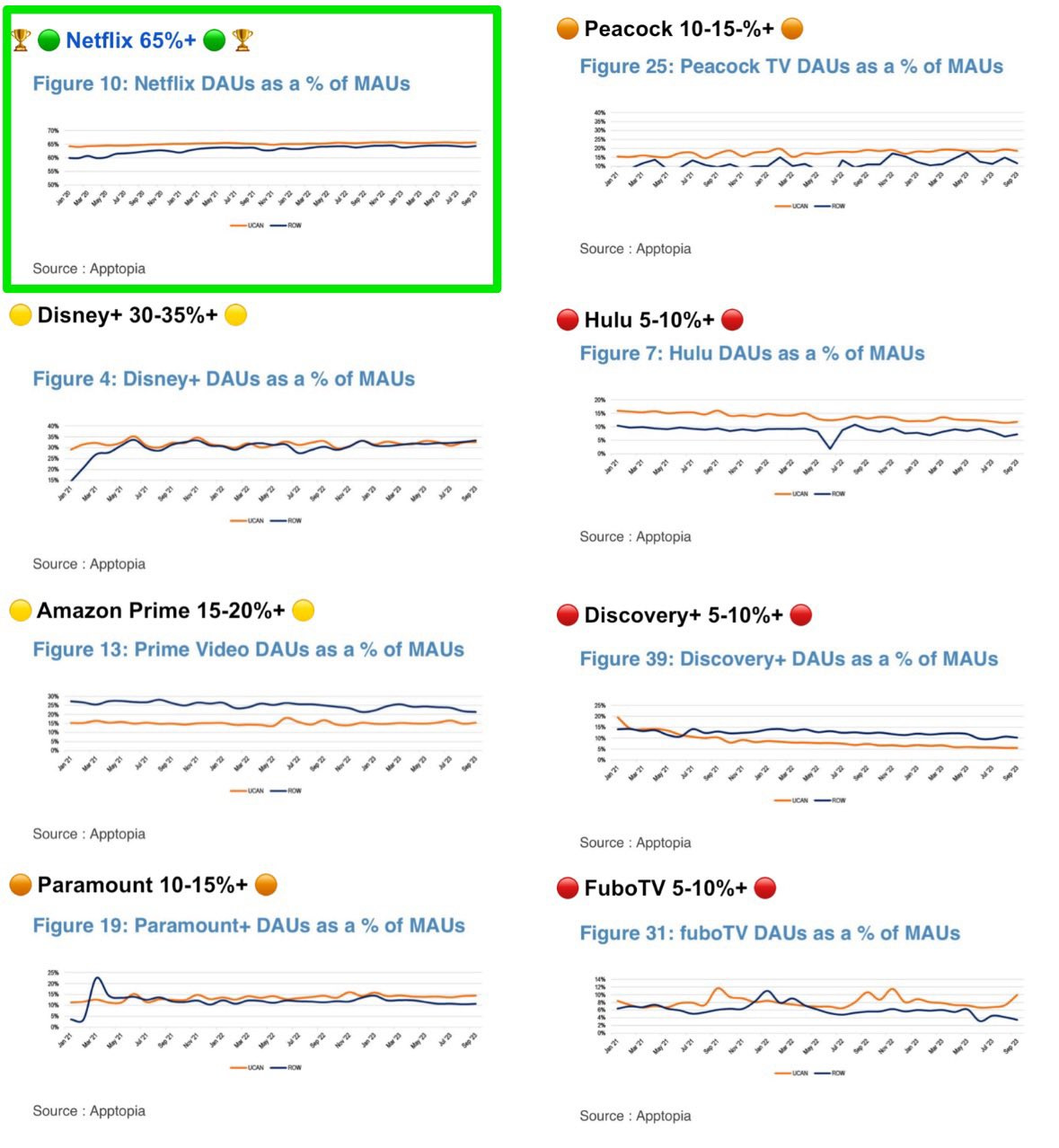

On the other hand, Netflix continues to spend by far the most on streaming content. Their technology and the user experience is widely accepted to be superior. And not surprisingly, the result is their subscriber engagement dwarfs that of their streaming competitors. As you can see below, Netflix dominates the field in terms of U.S. TV screen time.

And this graphic shows the percent of a service’s monthly active users who are also daily active users. The higher the better.

As you can see, an estimated 65%+ of Netflix’s MAUs are DAUs and it drops off very hard after that. If most of your subscribers aren’t watching your service very much, how receptive will they be to the price increases you need to—forget about making your service better—just break even? This engagement advantage explains why Netflix has been able to raise its UCAN ARM at an incredible 7.6% annual pace for the last 10 years—pricing power it’s competitors can only dream of—and yet still has the lowest churn rates—another thing it’s competitors can only dream of.

So where is the puck going? I would be cautious about prospects for any streaming service not named Netflix. Some services are making their already inferior value propositions worse while Netflix is keeping it’s already superior value proposition stable or arguably improving it. The gap between them seems to be widening. I would not want to bet on that trend reversing. Can anyone say with confidence that the licensing of of once-exclusive content to Netflix is going to be limited? Netflix management does not seem to think so, given their “As the competitive environment evolves” comment that I quoted above. And the more studios that offer licensed content to Netflix, the more supply there is, the less Netflix will need to pay for it.

With less content spending, higher prices, and licensing revenue, competing services might approach breakeven but making the value propositions worse makes it harder to grow subscribers or continue raising prices. What if subscriber counts begin to weaken requiring even less content spending, higher prices, and/or more licensing to maintain breakeven profitability? Every step in that direction makes the next step in that direction more likely. I don’t know how many of these services are viable over the long-term, but it’s not as many as we have today. On the other hand, Netflix will get much bigger, more profitable, and more cash generative over time.

I’ll save my updated financial and valuation discussion, including long-term margins, share repurchases, and the scenario analysis, for next time.

Disclosure: Long NFLX

Disclaimer: This post is for entertainment purposes only and is not a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Everything I write could be completely wrong and the stock I’m writing about could go to $0. Rely entirely on your own research and investment judgement.