Netflix: To the Victor Go the Spoils

Netflix won, peers are retrenching, the runway is huge, and the stock is cheap.

Netflix reported its first-quarter results on Tuesday. Here’s Ted and Greg’s shareholder letter and the transcript, both of which I think are must-reads.

For context, this is the first quarter without Reed as co-CEO but you wouldn’t know it by the vibe of the letter or the answers on the earnings call. Management’s tone and message were of the same flavor that I’ve gotten used to over the years with Reed in charge as CEO or co-CEO. That shouldn’t be surprising because these three have been running the business together for some time.

As for the quarter itself, there wasn’t much surprising. Revenue was as expected, margins were a bit better, and free cash flow of $2.1 billion is starting to ramp. I could go through all the metrics for these 90 days but frankly, whether revenue growth or margins came in 100 bps better or worse than expected or quarterly EPS beat or missed is really not that relevant for long-term shareholders. What is relevant are any new data points or learnings that provide greater clarity or confidence into the extent to which Netflix can live up to its long-term potential as the global SVOD leader and how that will translate into free cash flow over time. From that perspective, here is what I found important.

Early Paid Sharing Results

The first-quarter launch of paid sharing in four countries, including Canada, seems like a promising leading indicator for the broader rollout in the U.S. and elsewhere that’s now been pushed back to the second-quarter. As expected, paid sharing generates an initial cancel response as it is effectively a price increase. That played out in Canada but as sharers signed up for their own accounts or signed on as “extra members,” things improved. Paid memberships, not counting extra members, and revenue now exceed pre-paid sharing rollout levels. And Canadian revenue growth has accelerated and now exceeds U.S. revenue growth. What seems like a 2-3 month delay in the broader paid sharing rollout should enable further tweaks and improvements to the process that should benefit the business. That seems well worth the brief delay.

Basic with Ads Monetization

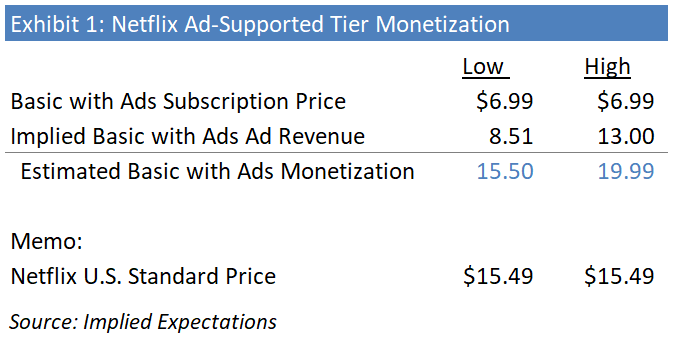

Basic with Ads (“BWA”) is already monetizing better than the $15.49 Standard plan in the U.S. This is great but not very surprising to me. For context, there had been fear that the lower priced ad tier would drive meaningful trade-down from Standard and Premium subs. But like I wrote about in Netflix: Some Ad-Supported Math (July 2022), I thought the ad tier was poised to monetize really well given 1) the strong monetization of competitive ad-supported tiers and 2) Netflix’s relative superiority on some of the key variables: engagement, ad load, CPM, and subscription price.

Given BWA is monetizing better than $15.49 and the subscription price is $6.99 in the U.S., that means the monthly ad revenue per member must be more than $8.50. But it’s probably not monetizing better than the $19.99 Premium tier yet or one would think they would have said that. Therefore, total monetization is probably between $15.50 and $19.99 per month, which means the ad piece of it would be between $8.51 and $13.00.

That seems really good considering BWA only launched in November—and getting into the ad business at all was only put in motion a year ago. And it should only increase as they improve targeting, measurement, and all the rest of it. I’ve said this before, but the speed at which Netflix executed on the ads launch is simply remarkable. That speed reminds me of Peloton CEO and former Netflix CFO Barry McCarthy’s comment last year that it would take months for Peloton to address its tech debt so it could A/B test on its website while that would have taken Netflix “1.5 days, even early on.” Netflix is simply world-class when it comes to execution at speed.

Given the excellent BWA monetization, management is actually making the offering better to encourage both new sign ups and a potential mix shift from other plans to BWA. It is boosting BWA video quality from 720p to 1080p and increasing concurrent steams from one to two. In fact, 1080p and two concurrent streams makes the BWA feature set equivalent to Standard but with ads. BWA is effectively becoming SWA for only $6.99 per month. If you’re a Standard sub paying $15.49, are you at all tempted to switch? Maybe the investor class reading a blog called Implied Expectations won’t be tempted, but there should be some trade down among the masses. Remember when investors worried about trade down not that long ago? Shareholders should be praying for it.

We can start with the $8.50 to $13.00 of ad monetization per user to then try to solve for the underlying variables of engagement, ad load, CPM, subscription price, and for the first time, the unknown level of leakage to advertising partners, notably Microsoft. Obviously, Netflix and Microsoft do not disclose the terms of their partnership.

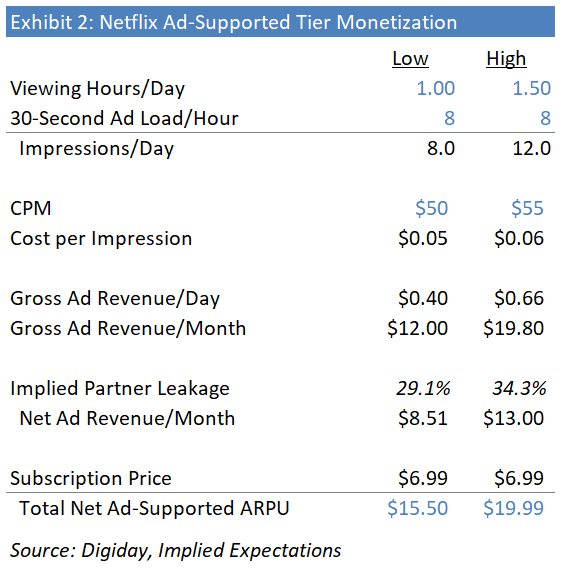

First, in 2019 former VP of Original Content Cindy Holland said the average Netflix subscriber watches Netflix two hours per day. However, that was before several competitive streaming launches so it’s likely somewhat lower than that today. After all, if that were still the case today despite the increased competition, I assume Netflix would have been eager to disclose it. For now, I’m penciling in 1.00-1.50 viewing hours per day for the BWA tier. That could end up a little on the low side.

We also know that the BWA ad load is about 4 minutes per hour, which is 8 30-second ad spots. And it sounds like CPMs are $55.

Exhibit 2 shows some quick math that puts those variables together and results in an estimated $12.00-$19.80 of gross monthly ad revenue per U.S. BWA sub. So how do we get down to $8.51-$13.00? Microsoft needs to get paid. Likewise with Integral Ad Science and DoubleVerify who Netflix has partnered with to verify the viewability and traffic validity of the ads. Management is almost certainly citing net monetization after partner revenue share.

As you can see, the above assumptions would back into a 29%-34% of partner take rate of gross ad revenue, which seems plausible to me. If you assume higher viewing hours, ad load, or CPM while keeping total monetization between $15.50 to $19.99, then the implied partner take would have to increase.

My guess is BWA monetization continues to improve over time with better targeting, verification, and measurability and sooner or later it monetizes better than the $19.99 Premium tier. At that point, we might see management improve the ad tier offering once again to Ultra HD or 4K and four concurrent streams. After all, if it is monetizing better than Premium and everything else, why not try to tempt Premium subs to switch to the ad tier, which would effectively be PWA at that point. A well-monetizing ad tier could also give management more headroom to raise prices on the ad-free tier since the risk of subscribers trading down is really no risk at all (although the risk of someone cancelling altogether remains).

Netflix seems to have the sort of culture that would prefer to build or buy the ad technology when possible rather than partner indefinitely. Why? Well, it seems clear the only reason they partnered at all was because they wanted to launch the ad tier as fast as possible. It couldn’t be done in-house in the desired time frame. As Netflix develops the expertise internally, it would be surprising if they did not take all of this in-house. For one thing, Netflix’s whole strategy revolves around having fixed costs that scale globally over time. Look at content. Tech spend. Marketing. Everything scales beautifully as they layer additional revenue on top of costs that don’t need to grow nearly as quickly. And look how unwilling they have been thus far to license live sports, which has been subject to meaningfully escalating rights fees over time. That’s the opposite of fixed cost content that scales, so they have avoided it thus far (although never say never if they can monetize ads better than others).

And considering how large Netflix’s ad business could be in the fullness of time with better targeting, verification, measurement, and programmatic features, the advertising innovations that are on the road map, a strong probability of a FAST offering (free ad-supported television), and potential for more ad inventory supporting live sports one day, it’s not surprising Netflix would pursue flipping this variable cost into more of a fixed cost when feasible. Simply put, Netflix seems likely to bring the ad tech in-house when its two-year deal with Microsoft comes up for renewal. If that linked story is accurate, that would remove a large amount of the partner leakage and let more of the gross ad revenue fall into Netflix’s lap.

International Price Cuts

The 20%-60% cuts in subscription prices in India have really helped accelerate growth there. There’s always fear that this sort of move suggests Netflix is failing in a certain market, but it’s better looked at as an optimization. Since those price cuts in India in December of 2021, the engagement has grown 30% year-over-year and constant currency revenue growth has accelerated from 19% in 2021 to 24% in 2022. The lesson is don’t focus entirely on either subs or ARM but on the interplay between them, which can drive revenue maximization. Management took those lessons and cut prices in 116 other smaller countries in February, which I think contributed to the stock’s weakness in February and early March. But if past is prologue, it should be a revenue maximizing decision over time.

Content Spending

Cash content spending is going to fall a little short of $17 billion this year, which led management to increase its 2023 free cash flow guidance from $3.0 billion to $3.5 billion.

A really big and important long-term question about Netflix is “How much revenue can a given level of content spending support?” Netflix has $32 billion of trailing revenue today on 233 million paid memberships but we know there are really over 333 million households using Netflix, including over 100 million who aren’t paying for it yet. Those 100 million at the current global ARM rate of $11.70 per month would bring in at least $14 billion of additional annual revenue if fully monetized. Therefore, it might be fair to say last year’s content amortization of $14 billion—amortization reflects what’s actually on the service, which is what matters here, as opposed to cash spending, which mostly reflects production—can probably support somewhere between $32 billion and $46 billion of revenue today.

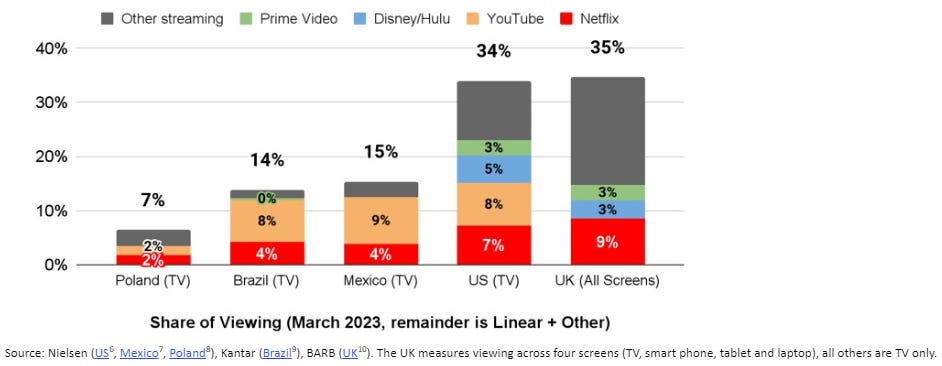

That is considerable, but I think Netflix should be able to leverage its content spending even better over time as streaming continues to take share from linear. That should gradually drive Netflix’s share of overall screen time higher—its a little less than 10% in the U.S. and U.K. today and much lower around the world—which should justify greater pricing opportunities over time.

Simply put, you’re willing to pay more for what you use the most. Engagement → retention → pricing power. In my household, we pay $73 per month for YouTubeTV yet we watch Netflix more often. What does that suggest about how much we should be willing to pay for Netflix? Obviously, Netflix can’t raise prices anywhere near that much anytime soon, but I’m optimistic about their pricing headroom, especially as linear dies over time.

I’m fascinated by the same content/revenue question longer term. If Netflix has $100 billion of revenue one day, how much content amortization will that require? They will absolutely leverage this line as they have historically. Would content amortization be $20 billion? $25 billion? $30 billion? Any of those amounts alongside $100 billion of revenue would be consistent with huge operating margin expansion from current levels.

Debt

Management continues to target $10-$15 billion of gross debt on the balance sheet. I think that policy will start to look a bit silly when Netflix is approaching $10 billion or more of annual free cash flow in a couple years. I’d expect management to switch to a policy targeting a maximum net leverage ratio sooner or later. Maybe no more than 2.0x net debt to EBITDA. That would free up additional resources for growth or shareholder returns while still prudently capitalizing the business.

Management makes a big deal of reaching an investment grade credit rating. But what good is an investment grade credit rating if you don’t use it? My guess is they will increase borrowings over time as EBITDA scales but remain investment grade.

Long-Term Margins

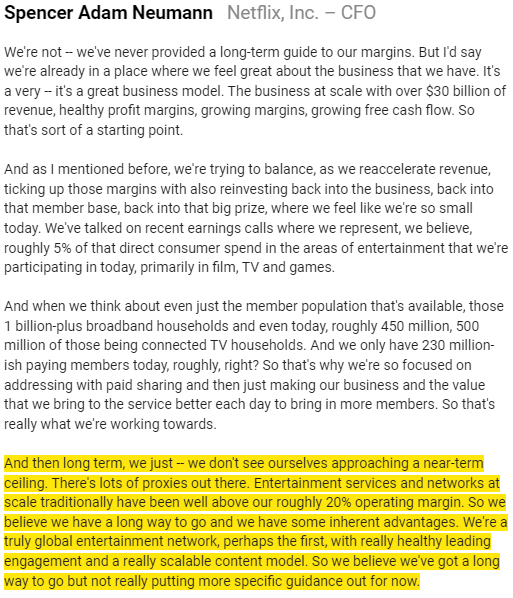

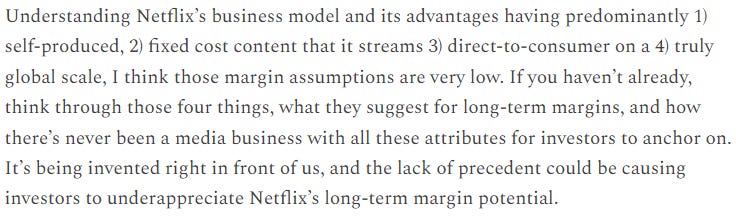

I have always expected huge operating margin expansion over the long term for Netflix—far higher than investors who may be anchoring on ~20% currently expect. CFO Spence Neumann, notwithstanding his consistent conservatism, alluded to Netflix’s advantages that should enable higher margins over time.

In Netflix: Turning on the Spigots (July 2022), I wrote:

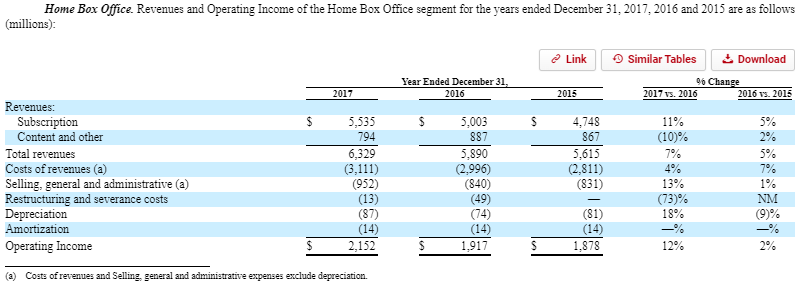

It is interesting to consider HBO, which had a 34% operating margin in 2017, the last year its detailed financials were disclosed. This segment income statement is from Time Warner’s 2017 10-K.

But there are some key differences between HBO then and Netflix today and tomorrow. HBO’s 34% operating margin reflected a U.S.-only business with a revenue scale that is 1/5th the size Netflix is today. It reflects a business model that was not direct-to-consumer but distributed via MVPDs (Comcast, Verizon, Charter, etc.) who naturally take their cut. It also reflects a higher mix of lower-margin licensed content than what Netflix should have in the long run. So it’s very easy to imagine Netflix today and in the future having much higher steady-state operating margins than 34%.

My last base case scenario posted in February, which I don’t expect to change materially when I update it shortly, had Netflix’s operating margins getting into 50%-60% territory in the long run. I think that’s super material to the forward returns long-term investors in Netflix can expect, but I’m in the minority on this. Where operating margins are in 10 or 15 years is just not relevant to most investors who are motivated by shorter-term factors like where they think the stock may trade over the next few months. As for me, I’m fully prepared to wait for those margins as long as my long-term thesis remains intact and the stock doesn’t become fully valued and less attractive relative to alternative uses of capital.

Big Picture

There’s a lot to be excited about with Netflix. The business is on the cusp of accelerating revenue growth as its paid sharing and ad businesses launch and begin to gain traction. The early signs from Canada and other markets suggest paid sharing initiatives will pay dividends. The ad business has potential to be very big and extremely profitable in the future. Free cash flow guidance has been raised to $3.5 billion this year and probably reaches something like $7 billion next year given guidance for flat cash content spending. And importantly, Netflix still has tremendous room to grow over time as broadband household and connected TV penetration inevitably increases. There are something like one billion broadband households ex-China and 450-500 million connected TV households—both of which will keep growing over time—versus Netflix’s 233 million paying subscribers today. Between that and the long-term pricing headroom I discussed above, Netflix has massive runway for revenue growth. All this and the stock is probably trading at a 5% free cash flow yield on 2024.

If it wasn’t clear years ago, it should be very clear today that Netflix has won streaming. No one else has the subscriber and revenue scale to put forth a firehose of new compelling content the way Netflix does. That drives engagement, which drives member acquisition and minimizes churn, which maximizes revenue, and the further ability to reinvest in content and technology. Netflix is big, profitable, and now highly cash generative. In contrast, Disney’s DTC segment is barely growing and lost $4 billion of segment operating income last year. Warner-Brothers Discovery’s DTC segment lost $3.7 billion last year even ignoring the $1.5 billion restructuring charge and just rebranded its service—rarely a sign a business is on the right path. Paramount lost a couple billion in its DTC segment as well. The list goes on.

These competitive streamers have finally come to terms that losing billions in an attempted subscriber land grab is not sustainable. They are retrenching, better balancing content across their other channels like linear, theatrical, and licensing. They can’t go all-in on streaming like Netflix can without imploding their legacy cash cow businesses. Further price increases are probably coming. But raising prices and monetizing more content on non-streaming channels is a great way to make their SVOD value propositions worse, which would make it harder to grow subscribers, leverage fixed costs, and gain that scale-driven exit velocity Netflix achieved.

To me, the only remaining question is really about valuation. What’s priced in at $325 per share, what are some plausible long-term outcomes for the business, and what do those outcomes imply about long-term shareholder returns from here in NFLX? I’ll try to answer those questions in my updated valuation post coming shortly.

Questions, comments, feedback? Am I missing something? impliedexpectations@gmail.com.

Disclosure: Long NFLX

Disclaimer: This post is for entertainment purposes only and is not a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Everything I write could be completely wrong and the stock I’m writing about could go to $0. Rely entirely on your own research and investment judgement.