Netflix: A Valuation Discussion

What do we have to believe to think NFLX is fairly priced at $435? What future would make it cheap? Or really, really cheap?

In this valuation oriented Netflix post, I’ll discuss a few things:

Netflix’s long-term subscriber and average revenue per member

Why it is hard for management to keep operating margins down

Why Netflix’s long-term margins are higher than most are willing to assume

The recent acceleration of share repurchases and how much of the company management might be able to retire if the stock remains flat

A long-term scenario analysis with five different outcomes plus a Priced In scenario—a reverse DCF—and corresponding valuations of the business based on those scenarios (a PDF with screenshots for IE subs; the downloadable Excel model for IE with Models subs)

A discussion of why this opportunity exists

Revenue

When I think about Netflix’s revenue potential, I think about the long-term opportunity to penetrate into more global broadband households. There are an estimated 1.6-1.7 billion households ex-China and ex-Russia (“ex-C&R”) and 600-650 million are thought to be broadband households today. That’s a broadband penetration rate close to 40%.

I assume the number of households grows at the long-term population growth rate of about 0.9%. So that gets the ex-C&R figure to almost 2.0 billion by 2042. I assume the global broadband penetration rate gets to the mid-80%s by then (99% in UCAN and 85% elsewhere; if you have a meaningfully different view on this, please let me know). So that would suggest almost 1.7 billion broadband households. Again, that compares to 600-650 million today, of which Netflix is being watched in something like 300-350 million homes, of which 247 million are currently paying. I also assume there is no meaningful difference between broadband homes and connected TV homes by then.

So big picture, Netflix’s household TAM is going to grow a lot over time. And what are these broadband households going to be watching on their TVs or iPads or headsets or 3D hologram projection glasses or whatever else? It’s not going to be linear TV, which won’t exist. It’s going to be streaming. And which company has the overwhelming scale advantage that positions it strongly to be the #1 streaming service in every market around the world ex-C&R? I don’t need to answer that. Netflix is already #1 around the world and its competitive position is only getting stronger, which I discussed in my last Netflix post.

So what percentage of broadband households is Netflix going to be in in 20 years? All we can do is estimate but one data point is pay-TV penetrated 80% of U.S. households at its peak. In my Base case, I assume UCAN goes from about 62% broadband household penetration today to 70% over that period. EMEA goes from 39% to 45%, LATAM goes from 41% to 50%, and APAC goes from 25% to 42%. That means that globally Netflix goes from 40% to 47% of global broadband households. With those assumptions, Netflix would have 790 million paid subscribers in 20 years, up from 247 million today.

The world is a big place. Tripling the subscriber base over time seems like a ton of growth, but I still don’t have a great answer for what the other 53% of broadband households ex-C&R will be streaming. For one thing, price is unlikely to remain an inhibiting factor. The lower cost advertising tier broadens Netflix to appeal to all demographics (yet still monetizes as well or better than Netflix’s Standard tier in the U.S.) and increasingly contributes to that. Further, there is potential for a free-ad supported offering. Management did not deny that is being considered when asked recently. And we all know services like Facebook and YouTube—popular, free ad-supported services— have close to 3 billion global monthly active users each. I can’t say Netflix could not approach similar levels over time after a free ad-supported option is available and flourishing. So while I stop at 47% broadband household penetration in my Base case looking out 20 years, I’m not quite sure why.

As for average revenue per member, Netflix is at $11.70 per month globally today. In my Base case, I have that getting up to $21.31 by 2042, which is a 3.1% CAGR. That is arguably no higher than inflation will be over this period. It’s also a downshift from the 3.9% annual pace since 2017. Certainly, this assumption is not aggressive.

Together, these subscriber and ARM assumptions would suggest Netflix will have just about $200 billion of streaming revenue in 20 years, up from about $34 billion this year.

Margins

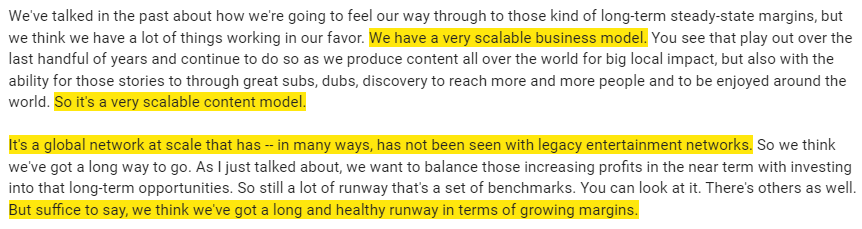

Given Netflix’s largely fixed cost operating model, I think it is hard for management to keep operating margins down. Consider this exhibit from the letter:

Despite massive increases in content spending, operating margins still marched higher year-after-year (until last year when the growth temporarily ran into a wall). This long-term margin expansion trend resumed this year and should end the year up 220 bps to 20%. That’s largely due to the fixed cost nature of its content deals, the temporary plateau in content amortization due to the writer’s strike, and the accelerating revenue growth thanks largely to paid sharing and the ad tier. And the margin expansion train should continue next year. Management guided to another 200-300 bps of expansion to 22%-23% next year, barring any wild swings in foreign exchange rates. Consider that this is happening despite meaningful investments in gaming—operating four acquired studios and at least two internally created ones—a live experiences offering, and building out advanced advertising capabilities. Operating margins would be expanding faster if it weren’t for these investments, which highlights the underlying operating leverage and why I said it’s hard to keep the margins down.

I believe Netflix’s long-term margins are chronically underestimated. Operating margins have been hovering near 20% for four years, so my sense is many market participants are anchoring on this. But when I play their story out over many years and assume reasonable revenue growth, it seems hard to prevent Netflix from reaching 50% operating margins if they want to do so. This model is all about scale and operating leverage. Netflix should have scale an order of magnitude higher than it has today. And most of its major expense buckets should see meaningful operating leverage. Content spending, marketing, G&A, and tech and dev don’t need to 5x or 6x just because revenue does. Management has done a phenomenal job minimizing the number of variable costs in the business.

The margins of cable networks are well-known. Some of them have had operating margins over 40%. Yet if you compare their businesses to Netflix, it becomes clear that Netflix should have higher margins at maturity. Netflix is the only “network” that operates direct-to-consumer by distributing largely self-produced content to a truly global audience at massive scale. DTC means Netflix gets to act as and capture the economics that otherwise flow to distributors like the MVPDs. The more the distributed content is self-produced, the higher margins should be. And finally, the ability to distribute much of the same content globally—when cable networks were fully distributed at 100 million households—is unprecedented. There’s never been a cable network that benefited from all of these things like Netflix does. That’s why I think Netflix should have higher margins at maturity than any cable network.

Management alludes to these business model advantages sometimes, but avoids giving long-term margin guidance. But the answer is there for anyone who is willing to think about it thoughtfully and use reasoning to reach a conclusion.

Buybacks

Netflix spent $2.5 billion on share repurchases last quarter, a sharp increase from the $400 million and $625 million it spent in the prior two quarters, respectively. The $2.5 billion was the result of repurchasing just under 6 million shares at an average price of $419 per share.

What’s interesting is their policy is to maintain two months worth of revenue on the balance sheet in cash and the remainder above that is eligible to be used for share repurchases. Occasionally, they discuss alternative possibilities for cash, such as tuck in content acquisitions, gaming acquisitions, etc. but none of that was mentioned on the call. So I think buybacks are probably the most likely use for now.

As of September 30th, Netflix had $7.9 billion of cash and short-term investments on the books. Two months of revenue is $5.7 billion based on last quarter’s revenue. So that leaves $2.2 billion available now. But based on their $6.5 billion of free cash flow guidance for 2023, they’re going to generate another $1.2 billion of cash in the current quarter. So there is probably over $3 billion available. The stock has been in the $300s this quarter, below the $419 per share average at which management repurchased shares last quarter (and below the $425 per share it paid during the month of August). So I would expect to see continued buybacks in the current quarter.

If my Base case were to play out, the company will generate well over $40 billion of free cash flow over the next five years, all of which could be used to retire shares while still maintaining its two months of revenue in cash. If the stock were to remain flat over that period, management could retire over 20% of the company—and at a very large discount to current fair value in my Base case.

Scenario Analysis

Here is the updated scenario analysis in PDF form. As usual, there are five different long-term scenarios plus a Priced In scenario, also known as a reverse DCF.

If you’d like the downloadable Excel file to play around with, please subscribe to IE with Models. If you do, e-mail me at impliedexpectations@gmail.com and I can issue you a pro-rata refund of your regular IE subscription.

And finally, the valuation summary that starts with the valuations derived from the model above:

Obviously, the future is uncertain. That is precisely why I model a wide range of outcomes. That said, it would be very disappointing to me if Netflix does not exceed the assumptions underlying the Super Bear case. That scenario assumes Netflix is in 36% of global broadband households in 20 years, which is actually lower than its estimated ~40% global broadband household penetration today. It also assumes ARM grows at a 2.6% CAGR, which might be no higher than long-term inflation and a downshift from its historical pricing power.

Why Does This Opportunity Exist?

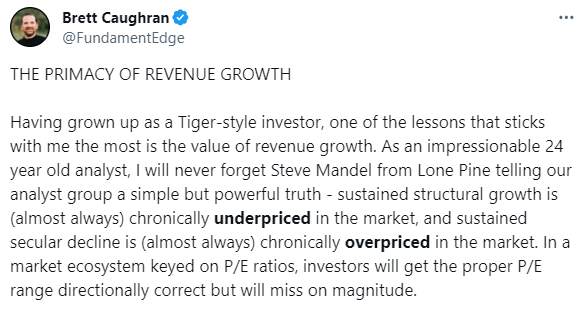

I think certain great secular growth companies tend to be chronically undervalued. Despite their growth profiles being generally or vaguely understood, the market fails to sufficiently pay up for them along the way. That might sound surprising because most people rely on heuristics like “high” multiples of 30x or 40x or higher earnings mean the stock is “expensive” and therefore unlikely to generate attractive returns. That seems like paying up. But that is a lazy rule of thumb that can be prone to error.

This reminds me of this tweet I recently read. Click on that image to open up the whole thread.

To be clear, I’m not saying it’s wise to pay huge prices for “growth” companies. Not at all. I’d assume that strategy would end in tears most of the time. What I am saying is there are limited exceptions or outliers where their huge long-term secular growth is chronically undervalued. In these rare cases, the expensive-looking multiples along the way just aren’t high enough to account for the prodigious cash flows that are coming. Obviously, it’s much easier to identify these exceptions in hindsight.

I remember writing about Chipotle in 2016 after its food safety crisis and how its stock had appreciated from $22 to $758 per share—a 34-bagger in less than 10 years—despite averaging an optically “high” earnings multiple of 43x along the way. And that you could have paid 183x earnings for CMG in 2007 and still compounded at a double-digit annualized rate since then. But this is the exception, not the rule. And the exceptions are hard to identify with conviction in advance. If you run around paying 183x earnings for every nicely growing company, you might go broke.

But Netflix has proven to be an exception throughout its history and I think that will continue. One might think, “Your Base case valuation is 15.8x trailing revenue? Come on.” But the person with that point of view is just anchoring on valuation heuristics. I would say that person needs to open their mind and thoughtfully consider the underlying assumptions that ultimately spits out a present valuation that happens to be a 15.8x trailing revenue multiple. What needs to happen over the next couple decades for that valuation to be fair value? If you think about it, there’s really no such thing as a low or high multiple of any metric that necessarily corresponds with high or low forward returns—it always depends entirely on the future. You can overpay for something paying 3x earnings and you can underpay by paying 100x earnings. Like most things in life, it depends.

So what is your best guess about Netflix’s future? Yours will differ from mine but that’s expected. That’s why I model a wide range of outcomes—to hopefully help you determine what you need to believe about Netflix’s future to conclude that the stock is attractive today.

As the creator of this meme, which I posted in my May valuation update, you know where I stand. But you should disagree if you have good reasons. If you do, let me know them!

Disclosure: Long NFLX

Disclaimer: This post is for entertainment purposes only and is not a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Everything I write could be completely wrong and the stock I’m writing about could go to $0. Rely entirely on your own research and investment judgement.